This is not about "Arab Shakespeare"

per se, but I want to write about this production, so I'll use the pretext that Shakespeare's

Merchant of Venice does depict an Arab: the Prince of Morocco. Though not as well known as Othello or Aaron the Moor from

Titus Andronicus, the Moorish suitor echoes them in certain ways, loving Portia "not wisely but too well." Doomed by his unseemly fascination with luxury commodities (gold!), he chooses the wrong casket (all that glitters!) and quickly leaves the scene.

The show I saw last weekend, by

Theatre for a New Audience (directed by the Yugoslavian-born Darko Tresnjak) at ArtsEmerson in Boston, made the strange decision to costume the Prince of Morocco (the fine African-American actor

Raphael Nash Thompson) as Gulf Arab royalty. Here he is flanked by Portia and her staff on the left, his own weird attendants (why does his head of security look like a flight attendant for Emirati Airlines?) on the right. Yes, that's an engraved sword he's presenting to Portia.

What's up with this? The role is unabashed ethnic caricature, and in modern productions a sort of turbaned Leo Africanus (or

Moorish Ambassador) getup

is typical. But playing the Prince this way let Tresnjak emphasize that this production was really about money as much as ethnic difference. Portia (Kate MacCluggage)'s feelings toward this suitor were ambiguous; she allowed herself several apparently heartfelt racist comments ("May all of his complexion woo me so!"), but she also seemed very attracted to him physically and comfortable flirting with him. The exotic sex appeal? The oil money? Both? Unlike her second suitor, he was a dignified and well-spoken man, a true member of the international aristocracy. In the end she may have been a bit disappointed (though she said otherwise) that he chose the wrong box, the one labeled "Who chooses me will get what many men desire." Childish, conformist Moor. What a pity.

The odd portrayal of the Moor ties in with what was so strange about the whole production. Tresnjak's Venice is made to resemble New York

circa 2008, a glitzy and fratty town where the tone is set by young investment bankers flying high on testosterone and Starbucks. The phones are smart and the Wall Street boys are too, trading the smug elbow jabs of financial capitalism at its most arrogant.

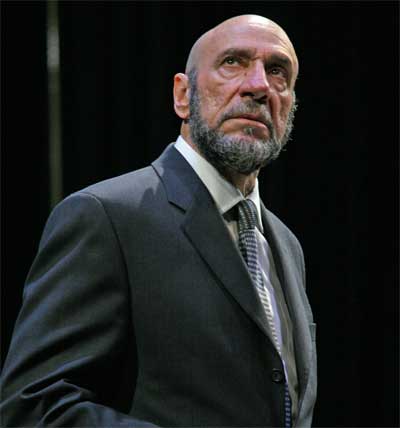

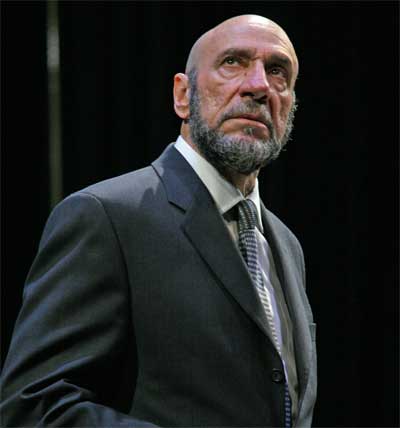

The setting has potential, but why isn't Shylock integrated into it? He is simply a man attached to his home and his daughter and his tribe: not even necessarily a banker. This makes him timeless, simply "a Jew." We never see him in anything like a work or office setting; his home is full of decontextualized Jewish kitsch (lanterns, candelabra, vague klezmer music), a weird break from the Apple-store sleekness (as my sister-in-law observed) of the rest of the set. This -- and the fact that Oscar winner F. Murray Abraham's acting towered over that of others, especially the milquetoast Portia -- makes the whole Wall Street setting with its 21st-century shenanigans suddenly irrelevant. The anti-Semitism is frat-boy cruel, but Shylock's response is simple atavism.

Everything else the production has going for it -- Portia's evident jealousy of her Bassanio's love for the closeted Antonio, Jessica's visibly growing nausea at the betrayal she has committed, Gobbo's rap antics -- is overshadowed by this basic failure to integrate the production's strongest character into its underlying premise. Incomplete allegory is the biggest risk of contemporary-dress adaptations; this show succumbs.

By the way, the ArtsEmerson folks all but announced that Al-Bassam's

Speaker's Progress is coming to Boston next fall. Stay tuned!